Thursday, December 21, 2023

Live in the Sun—Music that does a soul good.

Sunday, December 10, 2023

Urban Arts Gallery

Friday, December 01, 2023

Current Art Shows and a Thank You

Sunday, November 26, 2023

Monday, November 06, 2023

Angels of Music

Saturday, November 04, 2023

Upcoming Show: Femme Fatale at Urban Arts Gallery

What The World Needs Now Is More Rotten

|

| https://www.johnlydon.com |

I am a long-time fan of John Lydon. I greatly admire his creativity, his unwavering commitment to his wife, and his uncanny ability to cut through the crap.

Wednesday, November 01, 2023

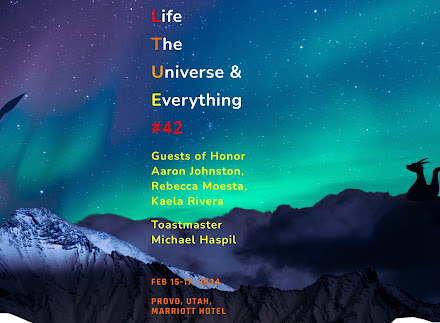

Upcoming Apearance: LTUE #42 in February 2024

Upcoming Publication: Book of Mormon ARTbook

Tuesday, October 31, 2023

Upcoming Publication: Dog Save the King, An LTUE Benefit Anthology, coming in 2025

Monday, September 18, 2023

Art in the Age of Algorithms: The Soul of Creation

Much like Tevya in Fiddler on the Roof, I’m struggling as the values and traditions of the art world change around me.

Monday, May 22, 2023

Tuesday, April 18, 2023

New Art: Portrait of a Mother

Digital Painting in Procreate

Artist Statement

As an artist, I have always been drawn to the power of the human spirit, and few expressions of this power are as profound as the love of a mother for her children. This painting is a tribute to the countless mothers who have sacrificed their time, energy, and love to raise their children with patience, dedication, and unwavering devotion.

New Art: The Return

"The Return"

©2023 Kevin Wasden

Digital Painting in Procreate

This painting was inspired by song lyrics by my friend, the amazingly talented Kira Gatiuan.

New Art: Aphrodite

Wednesday, February 08, 2023

Reflections on the Impact of AI on the Art World: Challenges and Opportunities

Around the turn of the millennium, as personal computers developed the capability to run more advanced programs, the art and illustration markets experienced a revolution. Programs such as Adobe Photoshop and Corel Paint suddenly enabled artists to create images at an unprecedented speed and scale. However, the impact of these technological breakthroughs also brought new challenges. The influx of new artists and the speed of production led to increased competition and decreased pay across much of the illustration industry. Artists were forced to adapt to new mediums and expectations.

Fast forward to today, and the art world is once again being shaken by digital technology, this time with the rise of artificial intelligence (AI) in the creation of art. With AI art generators, anyone can now create art with just a few words. This technology has ignited a deluge of new debates and controversies regarding the nature of art and originality.

Monday, January 30, 2023

Polarized Thinking: The Dangers of Thinking In Black-And-White

It's easy to get caught up in the habit of thinking in extremes. Whether it's politics, race, or simply concepts of right and wrong, we often seek to classify people and events into polar opposites. This way of thinking, known as polarized thinking, can have damaging consequences for both individuals and society as a whole.